http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/collections/projects/rhodo/skinner/

John Perkins

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/collections/projects/rhodo/skinner/

John Perkins

http://www.mikemaunsell.net/2008/01/concerned-irish-students-to.html

John Perkins

http://www.rhodogarden.com/Anun_kevatatsaleat/index.html

and some information on the use of azaleas in Finland

http://www.dendrologianseura.fi/rhodokerho/azabreed.html

John Perkins

There was some excellent research done in Europe in the 1970s by J. Heurshel and W. Horn where they identified six pairs of genes controlling flower in evergreen azaleas. It was all in German and I just have a few translated notes I got from Augie Kehr many years ago. Their study showed that flavenols which give that ivory color also seem to increase the "purpling" effect when anthocyanin pigments are present. Anthocyanins are water soluble but they control red, purple, and blue colors we see in many flowers. The exact flower color will depend upon the pH of the plant tissue, though. Flowers in rhododendrons are apparently buffered, so we can't change the pH of the soil and expect that will change the pH of the flower and thus the color. We can do that with hydrangeas, though.

Dealing with unexpressed anthocyanin pigments will add to the complexity, especially when trying to breed for yellow. Many white azaleas like 'Rose Greeley', 'Desiree', and kiusianum album have those hidden purple genes. The ability to produce flower color is recessive, so for a plant to have white flowers it must have two of those recessive genes. Unfortunately, purple flower color is a dominant gene and will totally dominate in crosses with salmon or red shades. It will often show up with abandon in future generations depending upon the whites one uses since only one of those purple genes needs to be present to get a purple flower.

The effect of flavenols on purple genes might explain why Joe Klimavicz's cross of 'Leopold Astrid' with 'Girard's Fuchsia' produced a seedling with a definite yellow color. 'Girard's Fuchsia' is probably that intense purple shade because it has a high concentration of flavenols which modified the pigment expression. 'Girard's Fuchsia' was probably not homozygous for purple so when those genes segregated out in 'Sandy Dandy', he still had the flavenols but no purple genes anymore. 'Sandy Dandy' is gorgeous and a very unique color... yellowish-cream with a bit of a pink blush. I picked one up at the 2006 Convention and it has buds for next spring. I haven't used it yet in hybridizing yet but maybe this year.

Good yellow rhododendrons often contain both flavenols and carotenoid pigments. Carotenoid pigments are insoluble in water, but those are the ones that provide the deep yellow color we see in native azaleas. I suspect the orange shades in some deciduous azaleas like calendulaceum might be the result of carotenoid pigments combined with anthocyanins but I am not sure. Every time I see that pink flush on a calendulaceum flower I suspect that both pigments are present. If anyone knows of some research in that area I would appreciate hearing about it. I know there was an article by Bob Griesbach (USDA) in the Winter 1987 ARS Journal on "Rhododendron Flower Color" that briefly discussed chlorophyll, flavenoids, and carotenoids in relation to flower color.

I agree that we need to build on Augie Kehr's work. My approach is to find hybrids between evergreen and deciduous azaleas that may already have genes for those carotenoid pigments... a.k.a. hybrids like 'Pryor Yellow' although that plant was sickly and has already died. I also think we need to get away from the deciduous azalea leaf quality as soon as possible since that will probably dominate those primary crosses. Most of the Azaleodendrons I have seen that are crosses of deciduous azaleas with rhododendrons have the worst looking foliage... very thin and ratty looking. They might look better if that foliage dropped off but it usually just hangs on looking awful.

If I can get plants that might have those carotenoid pigments in the background, I might first cross them with white azaleas that have a high concentration of flavenols and hopefully no genes for purple. Once I get a batch of those, I hope to cross the best "yellows" with one another and raise a huge batch of seedlings. Some might have higher concentrations of both pigments and then I can select for good evergreen foliage. That will likely take many generations... probably not in my lifetime either.

I know there will be sterility issues and selecting tetraploid parents will be important, especially since now know from Tom Ranney's research in the Fall 2007 ARS Journal that in addition to calendulaceum, plants we thought were diploid like austrinum and 'Admiral Semmes' are actually tetraploid. I now have concerns about your cross with 'Snow' since I suspect it is diploid and unfortunately, that means most of your seedlings will probably be triploid and sterile. I wish my 'Puck' was tetraploid, too, but I have no way to tell and I suspect that it is diploid. I expect to have lots of sterile plants with that cross as well. That just means we have to plan better when we make our crosses this spring. :-)

The route to a yellow evergreen azalea is complex, but Augie Kehr was heading in the right direction and we just need to continue his fine work. Wish he were still around to give us some advice, and that we could thank him for all he has done. He was such a great man and I feel honored to have know him!

Don Hyatt McLean, VA

http://homepage3.nifty.com/plantsandjapan/page019.html

John Perkins

http://www.plantanswers.com/grant6.htm

John and Sally Perkins

Salem, NH

http://www.garfield-conservatory.org/

John Perkins

John Perkins, this is a reminder for

Wed Feb 6 – Fri Feb 8, 2008

(Eastern Time)

The NEW Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, Boston, MA (map)

Calendar: ARS Massachusetts Chapter Calendar

Lectures, workshops, products, and networking for the Green Industry

More event details»

You are receiving this email at the account john.a.perkins@gmail.com because you are subscribed for reminders on calendar ARS Massachusetts Chapter Calendar.

To stop receiving these notifications, please log in to http://www.google.com/calendar/ and change your notification settings for this calendar.

John Perkins, this is a reminder for

Sat Jan 26 10am – 12pm

(Eastern Time)

770 Wapping Road, Portsmouth, RI (map)

Calendar: ARS Massachusetts Chapter Calendar

Potting up rooted cuttings

More event details»

You are receiving this email at the account john.a.perkins@gmail.com because you are subscribed for reminders on calendar ARS Massachusetts Chapter Calendar.

To stop receiving these notifications, please log in to http://www.google.com/calendar/ and change your notification settings for this calendar.

John Perkins, this is a reminder for

Sat Jan 26 10am – 12pm

(Eastern Time)

770 Wapping Road, Portsmouth, RI (map)

Calendar: ARS Massachusetts Chapter Calendar

Potting up rooted cuttings

More event details»

You are receiving this email at the account john.a.perkins@gmail.com because you are subscribed for reminders on calendar ARS Massachusetts Chapter Calendar.

To stop receiving these notifications, please log in to http://www.google.com/calendar/ and change your notification settings for this calendar.

John Perkins, this is a reminder for

Sun Jan 20 1:30pm – 3pm

(Eastern Time)

240 Beaver Street, Waltham, MA (map)

Calendar: ARS Massachusetts Chapter Calendar

Nan Sinton Speaker

More event details»

You are receiving this email at the account john.a.perkins@gmail.com because you are subscribed for reminders on calendar ARS Massachusetts Chapter Calendar.

To stop receiving these notifications, please log in to http://www.google.com/calendar/ and change your notification settings for this calendar.

Fred Knippel, Acton, MA

In this issue of THE ROSEBAY, I am going to introduce you to the summer-flowering deciduous azalea 'Golden Showers'. All too often people tend to gravitate to the evergreen elepidotes which, for the most part, all bloom about the same time, mostly from the end of May to early June, with a few exceptions. I have many of these same plants and who wouldn't? However, I also have about the same number of deciduous azalea varieties that bloom, following the elepidotes, until the end of July continuing into early August.

These plants particularly appeal to me because they bloom singly and, thus, enable me to pay them the individual attention they deserve. They are all distinctive and different, each to be enjoyed for its variety of plant habit, color of bloom, foliage and, in many cases, fragrance. I particularly like the summer-flowering azaleas. They do their thing without much competition from the rest of the Ericaceae family.

'Golden Showers', hybridized by Weston Nurseries, is one of my very favorites. Some years ago I obtained some cuttings of this plant and, as is all too common, the plant markers disappeared. When they first bloomed a couple of years later, I was mystified as to what they were. The buds were peachy as were the first flowers and neither looked like anything I had seen previously. Big mystery! Then the open flowers changed to yellow and then to white. At that point I was able to identify the plants as 'Golden Showers'.

I was very taken by the transition of color seen on the same plants, a progression that lasted for several weeks. In full sun 'Golden Showers' grows for me into a bushy and very floriferous plant with nice glossy green foliage which turns to a very attractive bronze before dropping in the fall. The flowers have a subtle vanilla fragrance that adds to their desirability. Like most of its cousins, 'Golden Showers' can be managed nicely by careful pruning. With a University of Minnesota rating of -24°F, the plant can be grown in even the coldest parts of New England. If you are fortunate enough to be able to drop into Weston Nurseries during the summer, you will see this lovely plant in person, along with many of their other beautiful summer-flowering azaleas.

Les Wyman, Hanover, MA

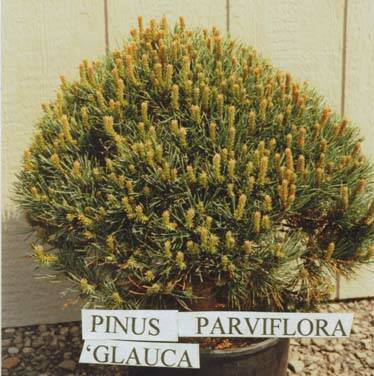

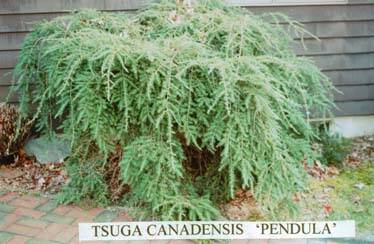

The name "Conifer" comes from Latin and means, "to bear cones". Cones are found on conifers at a certain age but it is interesting to learn that several conifers bear berry-like fruit, which botanically are cones. These are the junipers (cedars), yews and plum-yews. Another feature of these three genera is the fact that the sexes are separate and only female plants produce the berry-like cones.

Conifers are usually evergreen, producing the well-known needles of various shapes, sizes and colors. But some conifers are deciduous, shedding their leaves in the fall. In this group are the larch or tamarack (Larix), dawn redwood (Metasequoia), golden larch (Pseudolarix) and bald cypress (Taxodium). There is a golden-needled form of Metasequoia that is being offered for the first time this year. That plant is at the top of my "want list". Among the conifers are some of the smallest, largest, and oldest living plants known to man. The coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens), soaring an amazing 350 feet tall are found in California and Oregon are known to live over two thousand years. The bristle cone pines (Pinus aristata) of the Sierra Nevada Mountains at four thousand years old are usually considered the oldest living things. And there are miniature conifers that might reach two feet tall in 30 years!

There are more than 500 conifer species, distributed worldwide. They are invaluable for their timber and many other economic uses but gardeners value many species and cultivars for their year-round interest in the garden. The diversity of conifers for the landscape is endless. Nurserymen and other plant lovers around the world are devoted to the discovery and introduction of new selections that vary in size, rate of growth, form, color and texture. There has been special interest in the group of conifers known as "dwarf". The American Conifer Society has adopted as a guide, four size categories for conifers. Some plants will fit in one category but growing conditions vary tremendously and in one situation a plant might be very tiny while with more agreeable growing conditions the same plant might grow twice as fast. Size will vary due to the genetic makeup of a plant and cultural, climatic and regional factors.

Miniature conifers normally grow less than three inches a year. Dwarf conifers will grow at least three inches a year but less than six inches each year. Intermediate conifers will grow from six to twelve inches each year. Large conifers (often the species as found in nature) will usually grow more than twelve inches each year. Conifers are usually thought of as growing in the typical conical shape of Christmas trees but there are many other forms. Some conifers might be globose or rounded in general outline. A popular cultivar is Thuja occidentalis 'Globosa' (Globe American Arborvitae). I have an arborvitae cultivar named `Tiny Tim' that was planted in 1991. It is now eight inches tall and has never been pruned. Another bun-shaped plant is Chamaecyparis obtusa `Gold Sprite' (false-cypress). Our plant is twelve years old and is ten inches across and is about eight inches tall. It is difficult to choose a favorite plant but `Gold Sprite' is near the top of my list. Another miniature conifer in my garden is Picea rubens `Pocono', (Pocono red spruce). I bought this one in 1991 as a one-year graft. It grows about an inch each year.

The pendulous forms of conifers can be interesting. They are upright or mounding with varying degrees of weeping branches. My favorite in this group is Picea abies 'Pendula' (Weeping Norway Spruce). There are many cultivars of the Norway Spruce with this pendulous cultivar one of the most popular. The upright types might be very narrow, growing much taller than broad; these are fastigiate, columnar, narrow pyramids or narrow conical types. We are growing several rare cultivars of the Sciadopytis japonica (Japanese Umbrella-Pine) most becoming very tall and upright at maturity. Sid Waxman from the University of Connecticut introduced 'Wintergreen' Umbrella Pine a number of years ago, as the winter color is deeper green than other Japanese umbrella pines.

Then there are the prostrate conifers that might grow and creep flat on the ground. Pinus banksiana 'Schoodic' (Jack Pine) is a very rare form creeping flat on the ground. Another prostrate conifer is Tsuga canadensis 'Cole's Prostrate' (Canadian Hemlock). My plant is scarcely two inches tall and is four feet across at twenty years of age. It does best in a partially shaded situation. The spreaders grow wider than tall. Taxus baccata 'Repandens' (English Yew) is a spreading cultivar with deep green needles. This is a magnificent old time plant that could reach two feet tall and five or six feet wide in twenty years.

The irregular conifers have an erratic growth pattern. Picea pungens 'Pendula' (Colorado Spruce) might be very upright but could spread irregularly if left on its own without support. Height of this cultivar is determined by staking when the plant is young. Many gardeners prefer to shear and train their conifers. These are culturally altered into cones, pyramids, cubes and various other shapes. Often these forms are not pleasing to the eye, as the forms are very artificial in appearance. A good example is Taxus (Yew) which is often sheared and clipped. I sometimes say "Plant plastic bushes which can be purchased from any one of several department store outlets. No shearing required!"

Garden conifers come in a rainbow of year round colors that can be used with companion plants or in many garden situations. We recently planted a pine named `Chief Joseph' that has school bus yellow needles all winter but more typical green needles during the growing season. But getting back to the dwarf and miniature conifers. These groups excite much interest on the part of gardeners who often ask at the local garden center for plants that will be "low maintenance". This means "little or no pruning". The truth that gardeners should be aware of is that dwarfs and miniatures are slow growing but plants often might not be "dwarf" at maturity. So the rate of growth might be three inches a year which is true for the ubiquitous 'Alberta spruce' but this plant at maturity can be eight to twelve feet tall. So, even the slow-growing conifers do require maintenance, with pruning sometimes required to keep them at a desired size.

A few of my favorite dwarf and miniature conifers are: Chamaecyparis obtuse 'Gold Sprite' (False Cypress); Piece glauca 'Alberta Globe' (Alberta Globe White Spruce); Pinus strobus 'Soft Touch' (Soft Touch White Pine); Thuja occidentalis 'Tom Thumb' (Tom Thumb Arborvitae); Scidopitys japonica 'Richie's Cushion' (Richie's Cushion Umbrella-Pine); Abies koreana 'Silber Mavers' (Silver Mavers' Korean Fir).

Conifers are easy to grow in almost any well-drained garden soil. Miniature and dwarf forms seldom if ever require pruning. Insect and disease pests are seldom troublesome. Mites could be a problem on hemlocks and spruces if planted in a hot and dry situation, particularly when there is reflected sunshine. The hemlock wooly adelgid is a "new" pest of hemlock but I have not seen this insect on any of my hemlocks thus far. The cottony-like substance produced by the adelgid is easy to see and appears much like tiny 'Q-Tips' at the base of hemlock needles.

The American Conifer Society was founded sixteen years ago and has grown to a membership of fifteen hundred located in four regions. Members receive four issues of the Bulletin (magazine) full of conifer information, growing tips, articles on new or little-known cultivars and announcements that can be put to practical use in your own garden. Annual and Regional meetings are held each year. The auctions and plant sales at these meetings are popular and many conifers are sold to members. There is an annual seed exchange. For more information on conifers and the American Conifer Society write, call or e-mail Les Wyman, National membership chairman. 86 Tavern Waye, Hanson, MA 02341, email: hansplts@attbi.com

Les Wyman is the founder of Wyman Nursery, 135 Spring Street, Hanson, MA. He is now retired and collects conifers (200 cultivars); Rhododendrons (180 cultivars); Hollies, Azaleas and many rare and unusual plants. For twenty years he wrote "Grass Roots" a weekly gardening column which appeared in the Brockton Enterprise. He and his wife Marian were co-hosts of a gardening radio program on WATD, Marshfield, MA for five years

Susan B. Clark, Concord, MA

Rhodie growers share their landscapes with all manner of animals. Many animals are fond of rhodies and their companion plants, too, although for different reasons than gardeners! We all have a clear image of deer and their vices, but there are other animals that have a huge impact on us and our plants that we don't know very well. Voles are the most common mammals in Eastern Massachusetts, but their commonness doesn't make them familiar to most people.

Voles are small, tunneling rodents, neither mice nor moles. Their closest relative here is the muskrat; up north their cousins are the lemmings. Like their relatives, voles are herbivores, voracious ones who eat nuts, seeds, bulbs, bark, roots, and stems. If you have optimistically planted tulips or crocuses only to have none survive the winter, if your glorious hostas disappear or your stunning R. impeditum suddenly wilts and comes loose in your hand when you tug it, you have voles. If the ground under your birdfeeders is spongy with tunnels, you have voles. We have made their already luscious woodlands and meadows even more desirable by building stone walls, mulching heavily with bark and woodchips, feeding the birds, and planting gardens. Massachusetts Audubon estimates prime, natural vole territory supports more than 300 per acre ! How many must live on my cultivated acres of vole heaven?

Voles and lemmings form the microtine branch of the rodent family; all other North American rodents belong to the cricetine branch. Eastern Massachusetts has two common species, the Meadow Vole, Microtus pennsylvanicus, and the Southern Red-backed Vole, Clethrionomys gapperi. The Meadow Vole is between five to six inches long, with a one to two inch tail; they have soft reddish-brown hair above, silver-tipped hair below. They have bright black, beadlike eyes and small, visible ears. In fact, they look like young muskrats. Meadow Voles live in grasslands or grassy orchards and this is the vole that ravages the tomatoes, potatoes, carrots, and beets in my garden in our community field. When I pick up the intact, leafy top of a beet and find the entire inside eaten out, I have encountered a Meadow Vole.

Red-backed voles are smaller, four to six inches, and according to my various field guides, usually have a rust-red top, buff or greyish sides, and buff-white fur below. Every vole I see around our house in the woods of Concord (and I have seen many, alive and dead) is dark grey or grey-brown with a pale belly. Red-backs sometimes have a grey phase in the Northeast, which seems to be what we have here. Red-backs do less tunneling of their own, using chipmunk and mole tunnels, but also often running above ground. There is also the Pine Vole, Microtus pinetorum, which is distinguished by its softer mole-like fur, but is much more secretive and a deeper digger, "unlikely to be seen by the nonspecialist", as the naturalists at the Massachusetts Audubon Society put it.

All three voles are active day and night, all year. The maze of tunnels in the snow under your birdfeeders is the work of voles feeding above the frozen ground under the protective snow cover. They produce three to four litters of four babies a year. Do the math and you can see that one pair of voles can turn into over one hundred (if all survive and males and females are born in equal numbers) in one year.

Moles are not rodents at all, but are confused with voles because of the similarity of name, appearance, and tunneling habit. They are related only to shrews in the Order Insectivora. As the order name says, they are insectivores! They continuously tunnel as they look for earthworms and grubs; they rarely surface as they are essentially blind and quite timid. They are 'pests' only because we resent their 'disruptive' tunneling in our lawns as they hunt down their insect prey.

We have two species of moles, the Eastern mole, Scalopus aquaticus and the Star-nosed mole, Condylura cristata; both are three to eight inches long, short-tailed, and covered with marvelous, dense grey or black fur. They look very much alike except the Star-nosed mole has an astonishing fringe of fleshy projections on its naked pink nose. Since they live underground away from predators, they do not need to reproduce rapidly and only have one litter a year.

To tell a vole from a mole, you must notice the mole's lack of visible eyes and ears, the hairless snout, and the large, specialized forefeet, with their powerful digging claws on thick legs that are turned outward (moles do a kind of breaststroke through porous soil). Voles' eyes are big and black like a mouse and they have cute little mouse-like feet. Voles are much more likely to be seen since they are unafraid of daylight and the surface of the ground, are fond of birdseed, and are not blessed with a great, cautious intellect. Since they are rapid breeders, they are the ideal mainstay of the mammalian foodchain.

The gardener should welcome the mole, even if their tunnels mess up a lovely lawn; they are allies, for the most part. Voles, on the other hand, are plant eaters. Their tastes are varied and varying. One late winter they ate every Hosta 'Honeybells' I had, leaving only thumb-sized bits of rootplate for me to replant. Since 'Honeybells' is a vigorous Hosta, in a few years I had a good supply again and the rodents haven't touched them since then!

Usually voles seem to favor expensive, unusual plants or huge ones whose loss makes a real difference in the garden, like a four foot in diameter H. 'Blue Angel' or a ten-year old, magnificent H. nigrescens. A neighbor lost dozens of Astilbe one winter. Expensive bulbs like Camassia or ornamental onions and fancy lilies are likely targets. They favor some rhododendron roots but leave most alone. They are great bark strippers during a long, bitter winter when they can't get to food in the frozen ground; from my personal observation they favor Stewartia, Euonymous, and apples.

Now I plant my crocuses only in hardware cloth boxes with tops; I put hostas in hardware cloth "pots", but too often the voles just climb over the top and eat the roots anyway. We don't have enough predators to keep their population down. House cats, which love the easily caught voles, also eat ground-nesting birds, baby snakes and young reptiles. According to Massachusetts Audubon, domestic cats do much more harm than good to the environment and should never be allowed out. When using poison traps it's hard to be properly selective (I like having some chipmunks around) and I don't want the predators we do have to eat poisoned rodents. So I curse often and remind myself to admire their efficiency and prolificness and feel grateful that they haven't eaten everything — yet.

Sally Perkins, Salem, NH

I sort of know what hardiness means and how others define it. I know what a blasted flower pip looks like; a shriveled up blackened remnant of what could have been if not for a harsh combination of weather. I know what drought looks like, what winter burn looks like, bark split, Phytophthora, sun scald, leaf spot, stem die back, and frost damage. But is it hardy you ask? "That depends", I say.

Most rhododendron books define hardiness on the minimal temperature that a plant can endure and fully bloom. This definition works just fine if all one cares about is the bloom. Blooms are a bonus for 2 weeks out of a year. The plant has to look pretty darn impressive in bloom for that to be the only reason to keep it in my garden.

I consider plant hardiness as coming through the winter with healthy foliage and healthy roots. Cold hardiness requires that the plants have acclimated properly through the natural process of lengthening nights and cool temperatures to become dormant. This is an active metabolic process requiring adequate moisture and proper nutritional balance. Much more critical temperatures occur in spring after the ground has thawed and buds have swollen. At that point forward, the dormant temperature ratings are not relevant anymore. The temperature that a plant can endure without injury rises sharply. Even the hardiest R. dauricum will lose flower buds when a cold blast of Arctic air briefly descends in April. The wise plant knows to hold back from the urge to grow.

We have plants that are flower bud hardy for our winters and not foliage hardy. Case in point is the Hobbie hybrids with their R. forestii Repens Group background and lovely red tubular flowers. If only the foliage came through winter looking attractive. Most have moved on to other properties. 'Baden Baden' is the only one we have kept. If we had reliable snow cover I am sure it would be different.

On the other hand, we have plants that have never flowered and not only do we not care if they ever flower but we might even be disappointed if they do. R. pseudochrysanthum 'Blood Red' lost its interesting red pigment on the underside of the leaf when it flowered. The dense blue-green leaf forms of RR. impeditum, lysolepsis and litangense, often die back on the flowering branches creating an uneven, craggy habit. Many of the selections of R. yakushimanum x bureavii, such as 'Hatch's Small Clone' and 'B.L. Silver', have such lovely foliage and new growth that the flowers just seem to get in the way. Their foliage comes through winter like a champ without damage from snow loads or ice. R. williamsianum is a species listed in most books at -5°F but 2 different clones has flowered for us below -10°F since 1992. I think R. williamsianum is hardier than rated but the culprit for most New England gardens is the late spring freezing temperatures that damage the flower buds. Try the R. yakushimanum x williamsianum hybrids for a similar look with later bloom time. But then late spring freezes are rare on our property.

Living on Canobie Lake in Salem, New Hampshire gives us a distinct advantage or disadvantage depending on what someone's opinion of the cause of a rhododendron's demise. The majority of the tiny property is on a slope so there is good drainage both in soil and air: great for disease prevention, bad during drought. Mature white pines and hemlocks provide partial shade and natural mulch but also root competition. The winters are colder than the surrounding area when the ice covers the lake from mid-December to late March, but the summers are cooler, too. The January thaw rarely reopens enough of the lake to nudge plants out of dormancy. The spring-fed lake water modulates the temperatures so that late spring frosts and early autumn frosts are unusual. But spring doesn't start until the ice goes out and even then the spring is often downright cold. In contrast, the autumn is long and warm. It is difficult to generalize from my property to another about hardiness. We sit near the line for USDA zone 5b/6a just 30 miles north of Boston and 17 miles west of the cold Atlantic ocean. The rain/snow line often falls just north or just south of us which means the weatherman's guess is as good as mine and the snow cover is pretty unreliable. Our winter lows are normally -10° to -15°F.

Every year in the late fall, John and I will walk through the garden and put our predictive powers to the test. We take mental notes on the plants that are not doing well. The ones that will have a "rough go of it" through the long New England winter. For if a plant is not healthy going into winter it is a bad omen on it coming out alive. Often I think it is the unseen root system that is the problem. Rhododendrons can lose half their delicate fibrous root system over the winter. Freezing and thawing and the resultant heaving will wreak havoc on smaller plants. This will happen almost anywhere in the garden but is most likely in the sunnier locations or if the soil preparation has too much peat. An autumn drought is a dangerous precursor to winter stress. During the shortening days of the year a plant's vegetative and floral buds are triggered to go dormant and as long as there is moisture in the soil and the ground remains unfrozen the roots will continue to grow. Drought will put a stop to this all too important root growth at a critical time. Only the following spring will the destructive evidence of an autumn drought appear, as apparently healthy plants will fail to push growth. Did the roots die last fall? Did the plant fail to go dormant? Did the plant go dormant too early and dessicate over the long winter? Was it really not cold hardy?

We have a rule that a plant is not declared dead until June 22nd at which point a post-mortem is performed. The "scratch test" of scraping the bark away with the fingernail to expose a healthy green cambium layer usually fails. The plant is then dug and roots are examined as well as the bark. Figuring out why a plant died can be helpful on correcting cultural conditions. Last year a mature 'Canary Island' looked wonderful coming out of winter but never put on any growth and died by summer. The plant was in my neighbor's yard and despite gentle reminders that deep infrequent watering was best during a drought situation the habit of watering lightly was hard to break. The deep roots were probably dead before the winter ever happened. On post-mortem, we were sure we would find signs of Phytophthora but alas, it was just dead roots. There were no tell tale signs of red or brown streaks in the stem or in the main roots.

If a young plant dies in its first winter it is often due to "bark split". This may be the result of freezing at the cambium layer which happens when the ground is not frozen either early in winter or early in spring when a sudden cold snap descends upon us. We have seen it only on small plants that have not established a thick or mature bark layer. Similarly, grafted plants are most prone to graft failure under the conditions that foster bark split. Sometimes we will see girdling by mice or voles that find the delicate cambium layer a tasty morsel. It amazes me how long a plant can look nice in the spring completely girdled. Obviously, protecting young plants throughout their first year or two helps to reduce losses.

We have tried a few interesting materials and techniques to coddle rooted cuttings planted out much too soon compared to prudent practices. Small plants such as rooted cuttings are simply covered with appropriate mulch material after the ground is frozen. Salt marsh hay makes a great mulch material as it does not pack down but needs to be secured from blowing away with evergreen boughs. A cut up Christmas tree is excellent for this but we do not mulch if we are lucky enough to have snow cover by Christmas. For a few years we tried cylinders of sonatubes which are waxed heavy cardboard tubes in diameters of 6-12" used in constructing poured cement columns. Using a hacksaw to cut the tubes to a height a few inches taller than the plant the tube is secured with wire prior to ground freezing. The tubes provide a windbreak and a sun shelter but allow natural precipitation of snow or rain to fall. Additional insulation of salt marsh hay or pine needles provides a cushion to our unreliable snow cover. Roofing tarpaper stapled to form a tube and secured with stiff wire does a similar job and can be cut to size in order to protect larger plants transplanted very late in the season. Burlap is just as ugly and more expensive. Old plastic pots with mesh bottoms work well too. The trick is to remove the mulch or windbreaks at the right time. Too soon and wide temperature fluctuations can still occur. Too late and the ground remains frozen as the warm March sun creates temperature and water stress.

Plants that are marginally cold hardy come out of winter looking pretty sad and struggle to bloom or to put on new growth. If they bloom heavily they may exhibit signs of drought stress from insufficient roots or may flag quickly during a growth flush. Assuming a decent growing season they will look best by the fall when they have reestablished a good root system.

Plants that are marginally heat tolerant, the alpine species in particular, will look great coming out of winter and start to look a little peaked by July and be truly ugly by September 1st. Heat tolerance is not as much of a problem here on the lake as summer highs rarely reach into the 90's. If you are lucky enough to have a summer home in one of these locations, go ahead and try some of the fussier alpine species. R. ferrugineum would be my first pick as it has handsome glossy leaves on a compact plant and blooms later than most and sometimes blooms sporadically in the summer. For the same look in a hybrid plant 'Tottenham' and 'Myrtifolium' are much more forgiving.

I think heat tolerance may also be more a matter of roots. Alpine rhododendrons often are described as being found where there is bright light but not necessarily direct sunlight, cool soil, excellent drainage, and reliable soil moisture. This is a demanding condition to match. Soil temperatures can build up with the dark bark mulch that we use extensively. Even the north side of my house gets direct sun in the long days of summer. Ground covers such as Cornus canadensis, Tiarella cordifolia, and Phlox stolonifera actually keep the soil temperatures lower by the air cooling properties of transpiration but only as long as the soil remains moist enough to satisfy the needs of the ground cover as well as the rhododendrons. In alpine gardens the use of white or light colored stone as mulch does a fine job of reflecting light and heat, slowly warming up during the day and slowly giving off heat during the night. Surface layers of stones effectively preserve the moisture underneath. Larger stones buried in the ground may be a hindrance to growing corn in New England but not to growing alpines as the roots may grow under the stone into its cool moist environment.

Worse case scenarios are the marginally cold hardy plants that are not heat tolerant. They are usually dead by September 1st or it would be a blessing if they were.

So what would I recommend to try? Here are a few of my favorite ones.

First the lepidotes:

'April White' clear white and R. mucronulatum 'Cornell Pink' clear pink, are a lovely combination for early bloom with good contrasting fall color, too. 'Manitou' with its interesting color change from bud to full bloom has a better habit than 'Windbeam.' Of course I love lots of different variations of R. minus hybrids like 'Pioneer Silvery Pink,' 'Weston's Pink Diamond,' 'Dora Amateis,' 'April Snow,' and 'Grandma Matilda' which are all tough reliable performers. The species itself R. minus Carolinianum Group 'Epoch' or 'Gable's Album' are tough plants for sun and good drainage. The pale yellow-flowered dwarfs R. keiskei 'Yaku Fairy' and form cordifolia want a little shade. The R. keiskei hybrid 'Too Bee' with the most adorable dark pink flowers with red spotting is just too cute. 'Southland' with is salmon pink flowers and compact habit can fit into most any garden along with 'Ginny Gee.' And how can you go wrong with any of those charming R. keiskei x racemosum hybrids?

Elepidotes:

R. degronianum ssp. yakushimanum named forms such as 'Phetteplace,' 'Mist Maiden,' 'Ken Janeck,' 'Yaku Angel,' and King's dwarf are excellent foliage plants in order of plant size.

'Scarlet Romance' Mehlquist's strong red is good for its reliable bloom, dark foliage and contrasting brown buds. 'Henry's Red' will give you a big sprawling plant with that unusually deep red color but "nothing special" foliage. 'Hello Dolly,' 'Percy Wiseman,' and 'Vinecrest' are in decreasing order of interesting flower and foliage in the yellow/orange category.

R. degronianum var. tsukushimanium has the most wonderful pink flowers on top of dark green shiny leaves complete with a shiny brown indumentum on the showy underside. One can't go wrong with named smir-yaks like 'Dorothy Swift,' 'Ruth Davis,' 'Crete' and 'Today and Tomorrow' for great indumented foliage, habit, and reliable bloom. R. bureavii 'Lem's Form' and most R. bureavii hybrids do not need to bloom to earn their place in my garden with their rich brown indumentum but would like to stay out of full sun.

Evergreen Azaleas:

I do not avidly collect evergreen azaleas so my recommendations are limited. Not all the North Tisbury azaleas perform well but 'Michael Hill' blooms cascades down a hillside.

R. yedoense var. poukhanense and named forms—This species has been used extensively to develop hardier evergreen azaleas but it is nice in its own right.

R. kiusianum—I have had no problem with hardiness in any of the 7 different cultivars I grow.

'Beni Suzume'—A late double orange-red Satsuki azalea that should not be hardy but it didn't read the book.

R. nakaharae—Both Polly Hill's low growing 'Mt. Seven Stars" and the taller 'Bovee Form' have strong orange-red color in June.

The Schroeder azaleas 'Holly's Late Pink,' 'Dr. James Dipple,' and 'Hoosier Peach' seem to have enough hardiness to bloom reliably for me.

Deciduous Azaleas:

These can have problems with green worms, azalea borer, rust and powdery mildew but the following are my recommendations.

'My Mary'—The multicolor orange and yellow flowers in a tall good foliaged upright shrub looks like the species R. austrinum.

'Marydel'—Very fragrant with a low stoloniferous growth habit makes this one of my favorite recommendations.

'Golden Lights'—My favorite Northern Lights azalea but recently I have been impressed with 'Mandarin Lights' and 'Northern Lights' with their healthy fall color.

'Weston's Innocence', 'Lollipop' and other fragrant Weston's introductions are perfect for summer at the lake.

R. cumberlandense 'Camp's Red'—Hard to beat for July color and I would recommend hybrids of the species too.

R. vaseyi —If you only have room for one deciduous azalea choose this one for its airy pink bloom or 'White Find' for pure white. Both have incredible multicolor fall foliage and are free of any of the insect or disease problems. If late spring frost is not a problem, R. schlippenbachii will reward you with even larger flowers but site it away from the afternoon sun.

C.J. Patterson, Norwell, MA

The topic we are about to discuss is a secret. You might want to lower the blinds and send the kids out to a movie before starting. It has, in the past, been considered cheating, and the funny mystic rites passed on to initiates in dribs and drabs. There was official sanction against it at truss shows, although we are now more enlightened and Rule X has been removed from the rulebook.

I speak, of course, of Winter Protection of Rhododendrons. OK, go ahead and laugh, but I am perfectly serious! Twenty years ago, Winter Protection was in the same no-no category that trimming leaves, leaf polish, and food coloring are in today. Why? Actually there was a good reason, believe it or not. Twenty years ago the members of the Massachusetts Chapter were just beginning to take the measure of our rhododendrons, trying many new and unknown varieties in our gardens and greenhouses. The rest of the rhododendron world was incredibly generous to us with both plants and advice, and while we were terribly grateful for the former, we soon found out that the latter often made no sense in our area. Plants that grew heartily when just "stuck in" often turned up their toes when given the T.L.C. recommended by the English or our West Coast friends. In particular we were most often warned that plants were "not hardy" for the East Coast. It was, it seemed, too cold for most rhododendrons in our neighborhood. (Even the famous Dr. David Leach made this mistake. If you consult his Rhododendrons of the World, you will see that he considered only a handful of species growable on the East Coast.) Because we wanted to grow rhododendrons out of doors, we became suspicious of any methods of ameliorating our New England weather. To say " yes, Mr. X grows that, but he protects it" would both sully the grower and condemn the variety. Gradually, as we became more familiar with our treasures and how to grow them in our uncertain weather, we have recognized winter protection for what it is - a very valuable tool for both the ambitious grower with irreplaceable rarities and the novice with his first few "tricky" varieties.

The techniques you will choose depend on three factors: the size of your plant, the current health of the plant, and which part of Winter you are trying to protect against. Some things can be done for just about any rhody, others are only suitable for special cases. Small plants are best treated en masse, in nursery beds, or otherwise herded together, as they have special needs and are also more vulnerable. All rhododendrons are hardier when mature than as babies.

For larger plants, there is a physical limit to protection; eventually you will have to come to grips with reality and let a plant either sink or swim. Reality usually sets in at about four feet. Health is an important factor too; a healthy plant is a hardy plant, or at least as hardy as it is gonna get. If you are going to try to sneak rhododendron rex past Ma Nature in Zone 6, you need to make it as happy and healthy as possible to have even a ghost of a chance. Which part of winter are you trying to defeat? If the plants are normally hardy in your area and you are simply giving them time to become established, that is fairly simple. If the plants are borderline hardy ones that just need a little help to get past the worst excesses of winter, that is also pretty easy in most cases. Perhaps you didn't get everything planted from the terrific end-of-season sale at your local rhody emporium and you need a place to stash them for the winter? Hey, no problem! But if you are thinking of a specimen plant of 'Dr. Calstocker' on your front lawn, you need a reality check, because Ma Nature will always be one step ahead of you. It's her job.

The simplest winter protection is a deep (four to six inches) fluffy mulch of whole or chopped (not ground!) oak leaves or salt marsh hay spread out over the root zone and snugged right up to the base of the plant. It is especially effective with seedlings and rooted cuttings, although it is useful for somewhat older plants as well. This mimics the protection that the mass of an older plant will give to its own root zone; it shades the soil and prevents rapid freezing and thawing, and it shades the stems on young plants to prevent bark split. This mulch can be applied right on top of your regular mulch as soon as the ground freezes, and should be taken away in the spring. If you are mulching a nursery bed full of young'uns from P4M, you can even tease a THIN layer of hay, or perhaps scatter some fresh pine needles over the leaves as well, which will give some protection from winter sun. This is not necessary if the beds have shading in the winter from high pines or from artificial sources, and in any case should never cover more than 50% of the leaf surface. This technique is contraindicated for large, dense, mature plants; the extra protection will only coax Mr. Vole to take up residence and you don't want that. Trust me on this.

Another good, easy technique for protecting a nursery bed is to erect either old-fashioned wooden snowfencing or lattice over the bed, like a cover, except that it is set eighteen inches to two feet above the ground - enough clearance to be able to reach in and check the plants or fluff up the mulch. For larger plants in a nursery row, I have seen snowfencing effective up to four feet above the ground; higher than that and the side wind tends to cancel out the benefits. The lattice can be removed in the summer, or left on all year for babies. You can think of this as a very tall mulch - it serves all of the same purposes, except to retain soil moisture, and works as well for medium sized plants as babies.

For hybridizers, a variation on this method can be very useful if you are using plants in your breeding program that are not quite hardy in your area. In a raised bed, plant your breeding stock with enough room to grow large enough to bud up. Now erect sides on top of your raised bed (you can use 1 X stock or outdoor plywood for this - it won't be in contact with the ground). Finish with snowfence or lattice on top. When you are done you will have a box, open at the top, but otherwise well protected from the weather.

There are two major problems with this setup; first, it is unsightly, and thus unsuited for high-profile spots in the garden, and second, it is very attractive to rodents and you will have to trap or bait inside the bed. This is particularly bad in good snow years; do not neglect this chore. I know it sounds like a lot of work, but I have known breeders to get a zone and a half extra this way. Does it go without saying that this is for plants that will bud up as reasonably compact plants - say, no more than 18 to twenty-four inches?

Perhaps your problem is not a nursery bed but a single plant in need of a little extra help? If the variety is one that you are not worried about the hardiness of, but just a plant planted late in the year, or maybe one whose top is not well balanced to its rootball, then the familiar "tent" made of burlap and stakes can be all that is needed. Sometimes in New England we suddenly get unusually dry, cold weather, often accompanied by cutting winds, and the frozen ground makes it difficult to put up a formal tent. If the plant you are protecting is small, it is easy to just lay a few pine boughs over it. But if you have a larger plant, two, three, or four feet tall, this obviously won't work. Instead, cut three or four young white pines about a foot taller than the plant to be protected, and lean them, teepee style, against the plant. Tie the top, arrange the branches for the best protection, and Presto! a tent that will shade and cut the wind until spring. Either of these "tents" will give you about half a zone of protection.

Of course the ultimate winter protection is a cold greenhouse, with nighttime temperatures maintained artificially with a heater. Drawbacks? Cost, for one: greenhouse, foundation, no-freeze water system, heater, cooling system, and the energy costs to run the thing. The less labor-intensive you make it, the more expensive it will be to build and run. How about a Quonset Hut? Less expensive than a true greenhouse, yes, but still pricey if all you want to protect is something smaller than a crop. In addition, you will still have to deal with overheating, temperature fluctuations, sunburn, and plant maintenance; many an amateur nurseryman has lost a crop by going on vacation in the winter, when nothing is happening.

So what we need is a place to keep a relatively small number of plants protected from the elements that will not cost an arm and a leg and will need a minimum of attention. What we need is a coldframe. Coldframes come in all sizes and shapes, but all are essentially the same thing - a pit dug in the ground, lined to shore up the sides so they don't cave in, and covered with a light-permeable lid with provision for ventilation and access for maintenance of the plants kept within. Properly built and maintained, they will last several lifetimes.

I have seen coldframes as big as barns; well, it was a barn, built over a pit twenty feet deep, with celestory windows for light and a big ramp for truck access. This overwintering facility for a large wholesale nursery provided the minimum of maintenance (mostly done by Ma Nature) with a maximum of flexibility, allowing plants to be shipped dormant over an extended period in the spring. If you have the good fortune to be given a tour of Wellesley College's greenhouses, don't miss their big walk-in coldframes. These were renovated about a decade ago by the Wellesley greenhouse staff to take advantage of advances in glazing technology, and they are now handsome units, clean and airy, striking envy in the hearts of their fellow gardeners.

Most of us, of course, don't need garage-sized coldframes but there is a bare minimum you must observe if it is to work for you. Simply put, by digging down into the earth you are tapping into the stored heat trapped in the earth at the end of the summer. Every day the sun shines, the glazing allows the frame to renew at least part of the heat released at night into the frame (the frame is opened a little every day so that the heat buildup is not too radical and harms the plants). Thus the bottom of the frame is the last place to freeze in the early winter and the first place to thaw in the early spring; in addition, temperature variations are evened out so there is no barksplit or heaving. To work, then, you need an air mass inside the frame that will be enough of a heat sink to perform this function without requiring such high temperatures that the plants will suffer. I saw brick lined frames in England that were no more than three feet by three feet, but of course, the last winter the English had was in 1962; they usually just have two Decembers and segue right to March. Here in New England, we need a bit more than that; I would say three-and-a-half feet wide by four to six feet long, and nine inches deep after backfill at a minimum.

The amount of protection such a frame will give depends on the materials the frame is made of, the glazing, and how deep the frame is dug. In my best coldframe, I kept an eighteen inch tall plant of Rhododendron edgeworthii, which went through several winters with minimum temperatures of between minus twelve and minus five degrees F. until voles made a nest out of it and killed it. I also had several "greenhouse" azaleas that were overwintered there and then brought in to the house in March to bloom. Neither the azaleas nor the rhody ever had any leaf damage or pip loss. Unfortunately that same extended family of Mr. Vole also reduced the azaleas to compost, giving me a hard lesson in vigilance or lack thereof. Rodent traps in coldframes should be checked at least twice a week, and bait stations checked and renewed every three weeks or so. Frames can be varmint-proofed, but it is expensive and a LOT of trouble.

Coldframe too much work? Or maybe you are going to Myrtle Beach for the month of January, and have no one to look after the frames in your absence? You could try a "Fred Frame" invented by our very own Fred Knippel. This is an extremely simple arrangement using some of the same principles as a coldframe, but it is more of a cold-storage technique, because once it is closed up, it cannot or should not be opened until spring. Choose a flat vegetationless spot at least six feet by ten feet, where water never collects in spring (this is important!). Using pressure-treated 2 by 12's, build a topless, bottomless "box" slightly less than four feet wide by eight feet long. Center it in your space, making sure that it sits firmly in contact with the ground. About mid-November in our area, fill the frame with your plants and water well. This will be their only watering all winter, so do it twice if you need to. Let the plants sit for a couple of days so the foliage will have a chance to dry. Then lay any tall plants over on their sides, and cover securely with a four by eight piece of outdoor plywood. You can use pressure-treated stuff but NOT new - let it weather before you use it. Do not forget Mr. Vole; leave bait at least, but a pan full of tomcat-used kitty litter has provided our best protection.

If we are still in Indian Summer mode when you set up your Fred Frame (the very best time to do it), you can leave it without its lid until colder weather comes. Eventually, though, the nights will get down to 25 degrees F. on a regular basis, and it will be time to put on the lid. Wait a week or two more now, until the ground freezes an inch or two, then cover top and sides with coarse woodchips. At my place in zone 6, we put six inches on top and about a foot on the sides. In colder zones, I think I would put more.

What is the theory behind this? It certainly allows for a slow cooldown and warmup, and keeps a nice even temperature during the winter. Does it keep the plants from freezing? I don't think so, although I do think it can't get too much below freezing because of the condition of the plants at the end of the winter, by which I mean near perfect. In any case, we are going to find out because I have acquired a remote sensing recording thermometer which will answer that question providing it will record through several inches of frozen woodchips. And frozen they will be, solid as the Rock, which is why I said it cannot be opened in winter. The exception to this is when we get a long January thaw with some decent open weather. The woodchips can then be shoveled off and the frame lid propped open or, better, taken off and the contents checked for rodent damage. Renew the bait and/or the kitty litter and reseal the frame. Do not wait for cold weather to return to shovel the chips back on. Try to get this all done in one day so that the plants (and the ground) hardly know that they have been disturbed. How much protection can you expect from this contraption? I honestly couldn't say, because we haven't reached its limit yet, but I would say that Zone 8 or so will probably be a practical limit (no citrus!).

Perhaps you have no beefy male to do your bidding? There is something else you can try. Although I have never personally done it, Blanchette Gardens in Carlisle, MA uses it to overwinter thousands of perennials with about a ninety percent success rate, depending on the winter. Once again, choose a flat unvegetated space where NO water will collect in winter or early spring, water your plants thoroughly, and let the foliage dry. Turn all the pots over on their sides, preferably in as compact and orderly a fashion as possible, and pointing in the same direction, biggest plants in the middle. Place rodent bait, traps, and/or kitty litter in several places. Cover first with one or more sheets of Microfoam, then with a stout single sheet of plastic (check for holes to avoid drips). The Microfoam and the topsheet must be large enough to cover the whole pile, with enough to spare to secure the sides with boards or bricks, or bury the edges under sand or woodchips. The best way is to use a combination of both techniques - boards or bricks to securely weight the edges against winter storms, sand or woodchips to completely seal the edges. Keep an eye out for rodent tunnels.

This technique will net you a half zone to maybe a zone of protection, and no guarantees of survival. Blanchette Gardens has used this for years, and although it is probably their best solution it still gives them mysterious die-offs despite the fact that nearly all of the plants are perfectly hardy.

There is one last thing I can describe. For many moons I have worked on the Chapter's exhibit for the MassHort spring show. If I have to be the one who holds the plants to be forced, I try to keep them in a deep coldframe or cold greenhouse so that they can be moved to the facility in Waltham no matter what the weather. One year our arrangements fell through at the last minute, and I got stuck holding the bag; one-and-a-half truckloads of mature, fully budded plants arrived at my place in the middle of a very raw November. Alas, there was no room in the inn! I was forced to find someplace out in the weather to keep them. They were much too big to put in a Fred Frame, and I really didn't trust the Microfoam.

The weather got progressively more miserable as I dithered over what to do, until Ma Nature stepped in. Bruce forecast a truly terrible Thanksgiving freeze; my exposed rootballs would be toast unless I did something P.D.Q. So I rounded up my long suffering hubby and we moved all of the plants under the shade of some very large white pines, and arranged them in a compact rectangle, grading them by size of rootball or pot. I started with the largest rootballs at one end and gradually got down to the smallest pots at the other end. Then the entire bunch were carefully covered up to their lower branches with coarse wood chips. This was a time-consuming job because I had to make sure no pockets of air were left between the pots; sometimes this required adding chips a trowel-full at a time. I finished with about a foot of chips all the way around.

In two days the temperature dropped like a rock, and only came up again after it had frozen the lot. Then it poured, soaking the pile with its captives, then dropped like a rock again. The whole bunch was one solid mass solidly welded to the ground. We had very bad weather all December that year, and when the time came to start moving plants into the greenhouse, we had to chop them out with a mattock. Plants were moved in all through January, and the weather continued to be miserable. BUT - we lost not a single plant to cold that year and we were unable to detect any loss of pips or buds, either. As an emergency method, it worked pretty well, but I wouldn't want to depend on it as a regular thing. As a caveat, it must be noted that we were not using any particularly tender plants that year, so as a method of gaining extra protection, I would not recommend it.

A few final thoughts on the subject. I am frequently asked about the anti-dessicant sprays that are sold to the uninitiated. Usually they are harmless, as long as you don't get any on the underside of the leaf, and they may even do some marginal good in a plant that was planted too close to winter to get its roots established. But usually I feel the same way about them that I do about SUV's. Many people justify getting them because they make them feel safer during winter driving; then this confidence leads to recklessness that puts them MORE at risk, not less (ask any state patrolman!). If you think you can bring your 'Dr. Calstocker' through the winter on your front lawn in Concord Massachusetts with anti-dessicants, think again.

I am also frequently asked if one could bring a hardy rhododendron through the winter by simply putting it outside during the day and bringing it in at night. "It's too late this year to plant that nice 'Duke of York' you sold us, the ground is frozen!" they say. "Couldn't we just move it outside during the day, and move it into the kitchen at night? Then we could plant it in spring when the weather gets better." Then they look at me with imploring faces and sad puppy-dog eyes. In a situation like that, I have no choice but to follow Nancy Reagan's advice; I smile and "Just Say No."

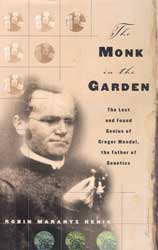

By Robin Marantz Henig

Hardcover: 292 p. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000. $24.00.

Paperback: Boston: Mariner Books (Houghton Mifflin), 2001. $14.00.

Reviewed by Ian E. M. Donovan, Pembroke, Massachusetts

Robin Marantz Henig makes science exciting as she sorts out myth from the facts as we know them in her retelling of the story of Gregor Mendel. It is a far cry from the simple tale we learned in high school or from college biology texts. The two settings for Marantz's retelling are Moravia and its revolutionary turmoil in the mid Nineteenth Century Austro-Hungarian Empire; second is the subsequent European rediscovery of Mendel's work on the edge of the Twentieth Century. Marantz tells us both stories.

Who emerges from this well researched study is a quiet, scholarly man, often wrestling with his own internal dragons that restrained him at each essential career step. Mendel failed at the family farm, at parish work, and at qualifying for higher teaching certification; he often took to bed for weeks at a time with a mysterious illness. He was rescued by a mentor who guided him into the St. Thomas monastery in Brunn, then the capital of Moravia. The monastery was run by free-thinking Augustinian monks of the Monravian Catholic Church, and it was the Abbot there who gave Mendel his opportunity at science. The Augustinian Order was a group of scholarly monks who wanted to pursue their bliss in the natural sciences, music, and physics, without interference from the Catholic Church or the state. And they did.

This monastery became Mendel's adult home and the location of his beloved glasshouse and garden. He eventually succeeded to the position and title of the monastery's Abbot, which he retained until his death in January 1884.

But what of his seven-year, carefully constructed experiments in breeding local Pisum sativum--pea--plants? This came about because the governing Bishop, during an inspection visit to the monastery, vetoed Mendel's breeding experiments in his quarters, using mice--mammals. Breeding was sex. Not appropriate in the Bishop's eyes--but plants were benign. No sex there!

Mendel delivered two lectures reporting his solitary experimental work to the Brunn Society in 1865. These were published the next year in their obscure journal. Mendel sent forty reprints to important European scientists, which were ignored. Charles Darwin, whose theoretical Origin of the Species was published in 1859, never even cut the pages on his copy of Mendel's paper. At his passing, all Mendel's papers and notebooks were burned!. So much for the work of the founder of genetic science.

Noel Sullivan, Late of Burnie, Tasmania, Australia

Reprinted, adapted and taxonomy updated, with permission, from The Rhododendron, March 1989, v.28:3. Official Journal of the Australian Rhododendron Society Inc.

Why hybridize?

To arrange the genetic makeup by the natural reproductive process to create a new plant better suited for the needs we have in mind, whether it be a bigger truss to win at shows or a plant designed for survival in a different climate. As for the adage ". . . that a hybrid is two species spoiled," surely what we can do in a few years might well happen in the millions of years it might take for the species involved to be in sufficient proximity for the same result to occur naturally, and for the resultant hybrid swarm to sort itself out. The result would be called a species.

Why bother when there are already too many hybrids to even remember them all? Apart from the sheer pleasure in this "do it yourself world", what about new, brighter colored flowers on a smaller plant with better foliage to allow a higher planting density in our now smaller "do it yourself" gardens?

Fruiting apple trees are hybrids developed to produce quality fruit and we know that seedlings grown from their pips will rarely attain this standard of excellence. Rhododendron hybrids were made for their floral attributes and the seeds they set with the help of the bees are just as unreliable. To even maintain the standard, they need the correct partner. But how do we find it?

Rhododendron hybridizing could not be termed an exact science for, as amateurs, we lack the financial resources to study and tabulate the many millions of genetic influences at work within a genus of nearly a thousand species. We would wish to know which genes are dominant or recessive for any characteristic, whether it may be height, leaf shape, color and number of flowers, etc., when any two species are crossed; and it will be different for any other two.

We lack sufficient data to program a computer to answer our dilemma. It might be called an art and with any art form there are guidelines for successful results. To cross pollinate rhododendrons without some knowledge of their genetic programming is like buying lottery tickets and expecting to be a consistent winner.

Start By Studying and Observing the Species

The species are the basic building blocks; by definition they are a set of fixed individual characteristics. Study a species, preferably with the textbook in hand, and note all the things that make it differ from other species. Look at R. griersonianum, used extensively in the production of warm reds, free from the blue cast seen in the old hardy hybrids. Take note of the flower color that bleaches rapidly in strong sunlight and which will also release its yellow fraction for strengthening other yellows. This is seen well in the hybrid 'Lascaux'--the bud, the leaf, the plant height and habit.

Now, with all this printed indelibly in your mind, look at its hybrid progeny, first and subsequent generations, and you will detect the dominant genetic characteristics that its offspring have inherited. BUT--but modified or even suppressed by the dominant genetic characteristics of the other parent. This knowledge and its application leads to successful hybridizing, for the function of genes is to program the living cells to build and maintain an organism to a predetermined design.

Genetic engineering will no doubt be used extensively in major profitable undertakings such as food, but probably never in the redesigning of rhododendrons. We will have to use the genes as they exist within the species.

Toward Developing a New Hybrid

The aim of this article is to enable the hybridizer to predict with some mathematical accuracy the results of any intended cross.

In the interests of brevity, to illustrate this method we will limit our instruction to the breeding of a hypothetical smaller plant with upright, if not tight, trusses in orange- yellow tones. This is our aim. It is somewhat difficult in that very few species, and here we are concerned with elepidotes, are orange. If we attempt to simulate orange from red and yellow, we must remember that flower color is not like an artist's palette but an ever-changing three dimensional pattern of living cells in tissue and sap. We must eschew the many reds with blue tints and even more that will be too large. Among warm reds are many small species, but most have few flowers in a lax truss. The yellows are fewer in number, some too tall, and the smaller they are, the laxer the truss, e.g., R. caloxanthum. All this is counter productive to our aim.

The obvious starting point is R. dichroanthum. It is a variable species; good in that it never exceeds two meters/six feet, and as the name suggests, has a flower of two colors--yellow overlaid in part by red--so that it appears orange. The drawback is the truss, very loose with four to eight flowers, usually less, and the color can be dull. All this is very dominant, so to achieve our aim we need some additive to lift the truss.

Lax trusses on larger plants can be very attractive for you look into the flowers. On smaller plants they can be disastrous for not many can be persuaded to lie on their backs so that they can fully enjoy all the floral details. Upright flowers, even in small trusses, are more desirable on plants below head height. An upright truss needs a strong and substantial rachis to support the overburden. The flowers should number ten or more, depending on their shape and size. The pedicels should be short and/or strong to hold the flowers upright, the more flowers the less this applies. These details become part of our genetic input.

What we need is a formula, a recipe as in cooking, listing the ingredients in proportions--one spoonful, fifty grams, two cupfuls, etc.--to make a cake. Our cake is that orange-flowered plant that we must construct from our building blocks, the species. But can we use a spoonful or a fraction of a species? The key lies in the hybrids.

To digress momentarily, Rothschild successfully crossed his 'Naomi' with yellow species to produce 'Idealist', 'Carita', and 'Lionel's Triumph'. A very simple and successful method of hybridizing is substitution of one parent with another, but be careful that the substitute differs only in degree. Thus 'Naomi' x 'Fabia' gave 'Ayer's Rock' and 'Naomi' x 'Champagne' gave 'Ripe Corn'. Therefore 'Naomi' x 'Lascaux' should be successful, provided you grow on sufficient offspring to exploit all the genetic possibilities.

Back to our theme. 'Lady Bessborough' is the union of two species: R. campylocarpum and R. discolor. Two units contributed genes to program a different unit or entity, which in turn can pass on those genes that it inherited from both parents. We could express this as a recipe. For 'Lady Bessborough' it is equal parts of both parents but, since the Lady is a unit, better expressed as R. campylocarpum 1/2, R. discolor 1/2.

Cross 'Lady Bessborough' with R. wardii. Again we unite two units and you finish with another unit made up of two halves, so the original halves on one side are now diluted to quarters. The formula now reads: R. campylocarpum 1/4, R. discolor 1/4, and R. wardii 1/2. This plant is 'Crest'.

Cross 'Crest' with R. yakushimanum and, following the rules above, the formula reads: R. campylocarpum ?, R. discolor ?, R. wardii 1/4, R. yakushimanum 1/2. We now use this formula to make an assessment of the genetic input in the areas that are of concern to us. Take color. Yellow genes have been provided: R. campylocarpum ? plus R. wardii 1/24 = total ? white, and R. discolor ? plus R. yakushimanum 1/2= total ? predicted color white with a trace of yellow. We could analyze the height in a similar manner and leaf shape, etc.

Writing this on New Year's Day [1989] in an unusual season, I go outside and examine this unnamed plant. It mimics the formula: the flower is a very pale yellow, the plant compact, and the leaf form follows the dominant parent, R. yakushimanum. Might this plant be a stepping stone towards our aim? What could we cross it with? We could cross it with anything provided that the total formula when analyzed tallied with the formula for our aim. This formula would show all the ingredients, the species, combined in the proportions to produce our hypothetical plant.

Let us look and see if there are any flowers out that may fill the bill. 'Dido'? No. 'Tortoiseshell Wonder'? No. What about this unnamed 'May Day' x 'Margaret Dunne' with bright orange but very open trusses of twelve flowers? Analysis of the total cross involving seven species gives a result of 7/16 for white and 9/16 for color, being 1/4 red and 1/4 yellow. Total analysis is a prediction that the average result of this cross suggests an orange flower in an open truss of twelve with the plant never exceeding three meters/nine and a half feet.

With any cross of this complexity, a large number of seedlings must be grown on to see all the genetic combinations. A more in-depth evaluation of the species involved in those proportions may reveal known dominant factors what may alter the final result, but what this percentage evaluation shows is that a visual possibility has become a mathematical probability. Did I make the cross? Of course. To honor the occasion, and if successful, I may even name it 'Day One'. But I won't grow on many seedlings for I have better irons in the fire and limited acreage, and I don't want to put my marriage into great jeopardy.

If you have been brave enough to read this far you will see that with this system you don't have to build with individual bricks. You merely locate two or more prefabricated units. With the ingredients in the correct proportions, slap them together and HEY, PRESTO!

Planning Your Cross

You should not expect to do this off the cuff. It should be planned like a military campaign; you need to assemble your troops or at least know where they are and when available, and you need a plan of attack.

It becomes obvious that you need textbooks or access to them for you will need details of the species. You must know the pedigree of the hybrids for you will notice that the order in which the components have been assembled dictates their proportions. The last added is always half of the total; if you need less it must be added earlier. For example, the extensive use of R. yakushimanum for dwarfing has shown that it invariably strips the color so the best use for this dwarfing keeps R. yakushimanum to below one quarter.

To make your plan, and having an aim, I find it easier to start with the main species involved--in our case R. dichroanthum. There may be more, but treat them separately, and from the Rhododendron Register [H. R. Fletcher. London: RHS, 1958, with annual updates.] list all the hybrids that are relevant to the aim. Make up a Graphic Display as illustrated on page 24. My Graphic Display for R. dichroanthum has many hybrids that have been left out of the illustration for simplicity. The Display, after photocopying, is kept as a permanent record and saves time, and wear and tear on the books when you have to look it all up again next week. The duplicates are used with colored pens in planning your campaign.

Tentative crosses are examined in various combinations and analysis shows that a certain combination has too much R. dichroanthum. We know from bitter experience that it will make the truss droop, so we attempt to find a better combination that sometimes does not exist. Knowing this, I have already made some of these halfway houses. While they won't be winners, they could be the vital link in the making of one.

Don't burn your experiments until you analyze them for future use. Don't use hybrids of vague parentage, e.g., 'Toucan', an R. eriogynum hybrid, orange-red. Obviously R. dichroanthum is in there . . . but what else? Displays may be made in any form. With many 'Bambi' crosses on the way, I have one with 'Bambi' on the bottom line.

The Graphic Display on page 24 suggests a battle plan and the analysis tells whether you have a winnable war. Let us, in brief, look at the Display but only the right hand side that deals with non-indumented plants. 'Fabia' x R. decorum has produced many plants, but which 'Fabia' and which R. decorum, and even which sibling?

'Tomeka' was used for its strong vermillion color. Bob Malone crossed it with 'Percy Wiseman' and we both grew on some seedlings. With some twenty flowered to date the results are pleasing. It has been given the provisional name 'Emu Valley' grex and predicted results have been confirmed. R. yakushimanum at 25% and R. decorum at 25% balance the height, lift the truss, and make 50% for white. The 50% color opens red and fades with the R. yakushimanum to yellow. The whites have cleared the opacity from 'Fabia' and the truss has good luminosity.

If we add 'Dido' to this blend, analysis shows that the color weakens as does the truss. 'G52' is an attempt to use the very dominant, low-mounded plant to get a better furnished truss than 'Cowslip'. We are assured of plant form and color, but will the truss stay up? Less chance with 'H41', for with R. dichroanthum at ?, its dominance for a lax truss will surely exert this influence.

Too little attention has been paid to the development of smaller hybrids with beautiful shapes and textures in the leaves. Such good-foliaged plants could be worthy rivals of dwarf conifers for pride of place in a garden, and flower as well. Better-furnished plants result when you use species that retain their leaves for more than one year.

An added bonus is indumentum, a beautiful but transient wooly coating on the new leaves that is permanent on the lower surfaces. This characteristic is genetically recessive and only passed on to the offspring when the other parent is similarly endowed. When listings of all the species with indumentum are assessed, we might group them in many ways.

Grouping Potential Parents

Perhaps the most meaningful assembly would be to group those from section Pontica, subsection Pontica with subsection Taliensia and the recently introduced R. pachysanthum from subsection Maculifera. Members of this group are smaller and all have pale or white flowers. There is trouble here with some having a short rachis, and crosses between members will not get you much color.

The other group contains the remainder, a mixed bag, but this is where most of the color and size is. Thus we include section Pontica, subsection Neriiflora and a few from subsection Campanulata, some subsection Arborea, and some big-leafed species. To save space, I will list but a few and hope that you get the message.

Group A. R. caucasicum, R. smirnowii, R. pachysanthum, R. adenogynum, R bureauvii, R. roxianum, R. elegantum, R. recurvoides, R. wasonii.

Group B. R. haematodes, R. mallotum, R. dichroanthum, R. lanatum, R. lacteum, R. griersonianum, R. macabeanum, R. falconeri, R. arboreum var. niveum, R. floribundum, R. simiarum.